Measuring progress using 'Point in Time Assessment' (PITA) bands

Most Insight schools now use some form of 'Point In Time Assessment' model for their main (teacher) assessment whereby pupils are classed as 'expected' or 'on-track' if they are keeping pace with the curriculum expectations, regardless of the time of year. This contrasts with steps-based systems, which involve a defined number of points per year (i.e. an expected rate of progress) and therefore have more in common with levels. This article goes into more detail on the differences and pros and cons of both approaches.

Whilst PITA-style approaches offer simplicity and clarity, confusion can arise when attempting to use such data to measure pupil progress. With steps-based models, we enter the desired number of points for the period in question - e.g. 1 point per term or 3 points per year - but no such expected rate exists for our PITA models because we expect most pupils to remain in the same band over time.

So, how do we measure pupil progress if we use a PITA-style approach to assessment?

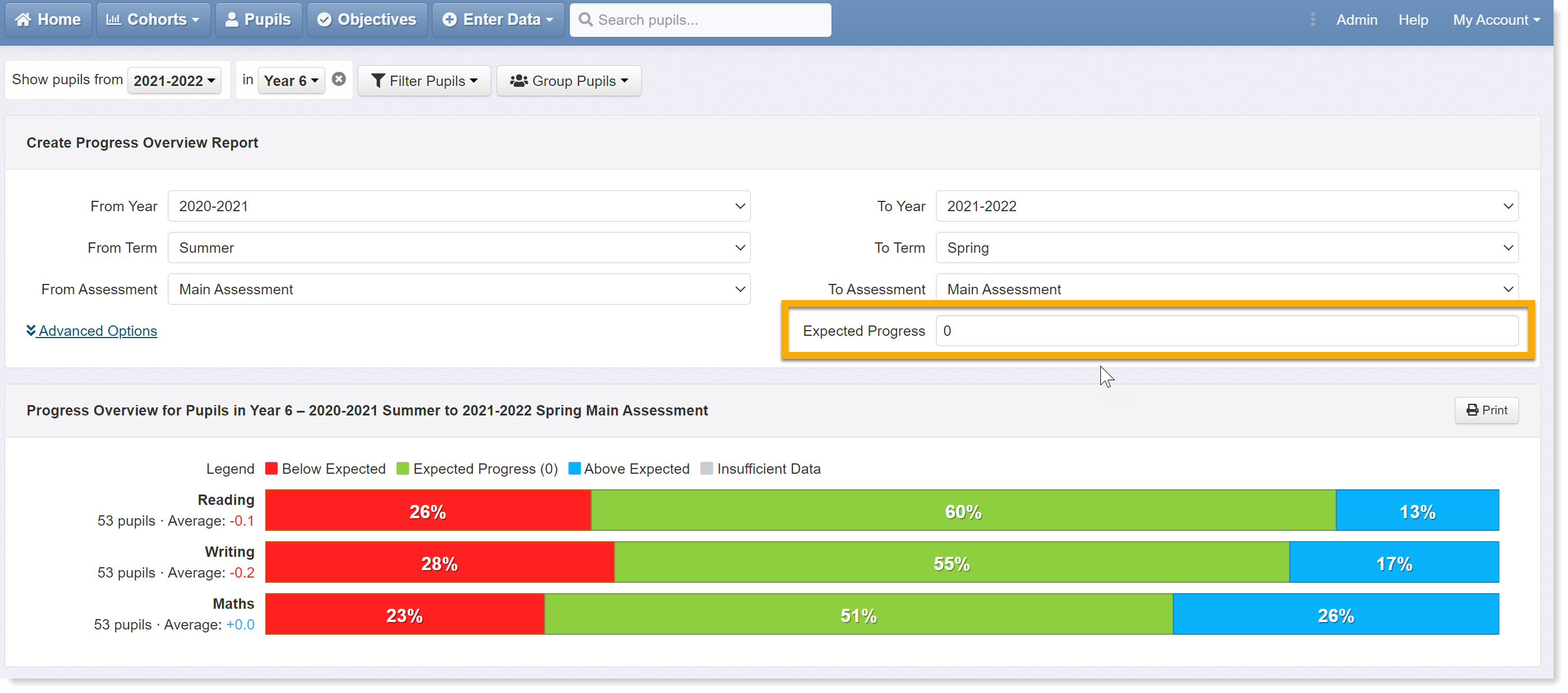

Insight's Progress Overview report is a flexible tool that is capable of handling most types of data: test scores, reading ages, steps, PITA bands, and even targets. You simply select data for the start point from the dropdowns on the left hand side, and data for the end point from the dropdowns on the right. Then you set an expected rate of progress.

By default, it compares main assessment data from last summer to the latest term and sets the expected rate to 0. If you use a steps-based model, you would change the expected progress value to reflect the number of points pupils are expected to make over the period in question, but if you use PITA then leave it as 0. By selecting 0, we are essentially saying that we do not expect pupils' assessments to change over time; that they should remain in the same band and doing so will be counted as making expected progress. This, of course, is a problematic assumption, which we will deal with below, but it works as a rule of thumb.

There are other cases where we would leave the expected rate as 0. For example, comparing pupils' KS1 results to their latest main assessment. Here, Insight will compare evaluations of the two mark schemes and equate, for example, 'expected' at KS1 with 'on-track' in the last assessment. Another case involves comparing steps- to PITA-style assessments, which may happen if a school chooses to convert from the former to the latter, or has legacy data from a previous system in a steps-format. Again, Insight compares the evaluation of each assessment, so if a pupil was previously assessed as 'Y2 Emerging' - and that was considered 'expected' at the selected time of year - and is currently 'on-track' (i.e. expected now) then the pupil is counted as having made expected progress (0). If Y2 Emerging was considered just below expectations at the selected time of year and the pupil is now assessed as on-track, then that would be counted as making more than expected progress (+1).

This is, therefore, a crude VA-style measure of progress similar to that used by the DfE at KS2. If pupils maintain standards over time, they will receive a score of 0, those that move up a band will receive a +1 score, whilst those that drop down a band are assigned a -1 score. Obviously, going up or down by more than one band will attract bigger positive and negative scores.

Each pupil included in the measure - those with valid assessments at both ends of the period - will receive an individual progress score as outlined above, and this can be averaged to give the cohort progress score shown to the left of the bars in the previous screenshot (e.g. -0.2 for writing). Whilst this average score may have some value, it is less meaningful than, say, the average change in standardised score or reading age, both of which are more suited to finer measurement.

One of the big flaws in this approach to measuring progress is the assumption that remaining in the same band over time equates to 'expected progress'. This may be the case for pupils that are already working at the expected standard, but is not the case for those that are working towards and need to catch up. It also means that those working at greater depth are at a ceiling and cannot be counted as having made more than expected progress. It is similar to the problems arising from the assumption of linear progression that plagued levels and still exists in steps-based approaches. No matter what data we use and what approach we take, all progress measures are flawed.

Further Reading

Measuring the progress of pupils working below expectations »